Spanish Literature of the Pre-Renaissance

Partly as a consequence of the remarkable artistic output generated in medieval Spain, partly because of the political realities lived in the peninsula following the decline of the Caliphate of Cordoba, Spanish artistic production in the XV century took a different direction to the dominating tendencies in much of Europe.

While the Aragonese crown geared its interests towards the Mediterranean Sea, successfully establishing itself as a mercantile player to be reckoned with in the international trade business, Castile-Leon remained mired in the feudal tradition that had turned a small county into the largest and arguably most powerful kingdom of the peninsula.

The result of this situation was that, while much of Europe, and specially the Italian states, experienced the changes that would lead to the modern world-view within which the Renaissance was possible, in the Spanish kingdoms political structures remained largely absolutist, traditional religion was hardly challenged and the environment under which artistic and social structures flourished in medieval Spain simply remained in place.

Thus, whether you be spending some months in Spain, it is important to bear in mind that the artistic production of the XV century bears little comparison to that of other countries, and must be examined on its own. It is in this context that singular works, such as La celestina must be considered.

Marquis de Santillana

One of the most significant literary figures of this period, which we might dub pre-Renaissance or post medieval Spain, was the Marquis of Santillana, a prominent member of the Castilian aristocracy of the time with close ties to the artistic establishment. His work serves as stepping stone to link the literary tradition of medieval Spain with the new forms that emerged in the XIV century, such as the Petrarchan sonnet.

Moreover, Santillana's interest in the popular forms, such as the serranillas, has merited him a place in the history of Spanish literature, especially after the XIX century. A worldly politician, the Marquis of Santillana's interest in the arts, both popular and highbrow, his innovative experiments in the Spanish language and his excursions into fictional prose and verse single him out as a rare example of Spanish Humanism in the XV century.

The impact of the Marquis of Santillana's work, or at least the influence of his family on the literary establishment of the time, becomes evident when we consider that the next outstanding poet of the century, Jorge Manrique, was none other than his great-nephew.

While chronologically two generations apart, Jorge Manrique and the Marquis of Santillana bear resemblance in more aspects than just their familial bond. Also an important member of the aristocracy, Jorge Manrique is best remembered for his Coplas a la muerte de su padre (Stanzas Upon His Father's Death), which incorporate a detached, more universal perspective of death, adopting a philosophical attitude linked to the Ubi Sunt and which ultimately seek consolation in metaphysical postulates.

The slow progression of the Christian kingdoms into the Humanism of the XVI century gained much strength with the unification of the crowns of Aragon and Castile-Leon in 1469. Spain, unified at last, began to move away from the Gothic aesthetic in favour of new ideas. And it was in this environment that, thirty years later, Fernando de Rojas followed on Jorge Manrique's footsteps and produced the emblematic piece which has been taken to signal the advent of Renaissance in Spain: La celestina.

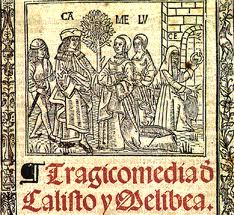

Originally titled The Tragicomedy of Calisto and Melibea, La celestina, as it is commonly known, is ostensibly a play in 21 acts, which, in practice, cannot, and was probably not meant to, be performed. The plot of La celestina is rather conventional: Calisto falls in love with Melibea, who rejects him, so he contracts the services of Celestina, a procuress, whose intervention indirectly gets Melibea to change her mind.

The tragic part of the story is that Calisto dies in the course of gaining Melibea's love, and consequently Melibea kills herself. The comic half, however, is the truly remarkable, given that the actions are not only light hearted but truly innovative in style. Celestina, the character, is cut from the same cloth as Trotaconventos, from The Book of Good Love, and the plot could be taken from any similar legend.

But the use of the dramatic structure to shape a narrative that is interested only in its own possibilities opened the way for the development of the Spanish novel during the XVI century - a most fruitful genre, which saw the rise to stardom of a certain Miguel de Cervantes Saavedra.